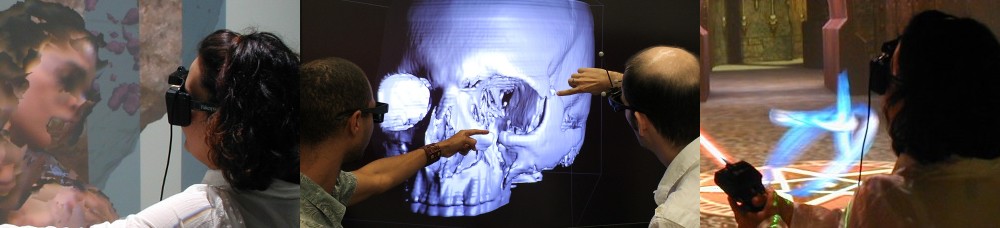

We had a couple of visitors from Intel this morning, who wanted to see how we use the CAVE to visualize and analyze Big Datatm. But I also wanted to show them some aspects of our 3D video / remote collaboration / tele-presence work, and since I had just recently implemented a new multi-camera calibration procedure for depth cameras (more on that in a future post), and the alignment between the three Kinects in the IDAV VR lab’s capture space is now better than it has ever been (including my previous 3D Video Capture With Three Kinects video), I figured I’d try something I hadn”t done before, namely remotely interacting with myself (see Figure 1).

Tag Archives: Vrui

Fighting black smear

Now that I’ve gotten my Oculus Rift DK2 (mostly) working with Vrui under Linux, I’ve encountered the dreaded artifact often referred to as “black smear.” While pixels on OLED screens have very fast switching times — orders of magnitude faster than LCD pixels — they still can’t switch from on to off and back instantaneously. This leads to a problem that’s hardly visible when viewing a normal screen, but very visible in a head-mounted display due to a phenomenon called “vestibulo-ocular reflex.”

Basically, our eyes have built-in image stabilizers: if we move our head, this motion is detected by the vestibular apparatus in the inner ear (our “sense of equilibrium”), and our eyes automatically move the opposite way to keep our gaze fixed on a fixed point in space (interestingly, this even happens with the eyes closed, or in total darkness).

Update on Vrui / Oculus Rift DK2

I’ve been getting a lot of questions about using the Rift DK2 under Linux with Vrui recently, so I figured I’d post a little progress report here instead of answering them individually.

The good news is that I have the DK2 working to the level of the DK1, i.e., I have orientational tracking, lens distortion correction, and chromatic aberration correction. I also have low persistence, but that came for free.

What I don’t have, and most probably won’t have until an official Linux SDK drops, is positional tracking. In order to replicate the work a team of computer vision experts at Oculus have been doing for the last year or so, I’d need a few clones and a time machine. That said, I am working on combining the DK1/DK2’s built-in IMU with other external tracking systems, such as Intersense IS-900 or NaturalPoint OptiTrack. That’s a much easier (but still tricky) problem, and would allow using the Rift as a headset for large-area VR. Probably not interesting for home users, but being able to walk around freely in an 18’x10’x7′ volume opens up entirely different VR applications.

I’m currently working hard on the next release of the Vrui toolkit (version 3.2-001), which will have at least the level of DK2 support that I have internally now (combined tracking might or might not make it, but that can already be faked, see 3D Video Capture With Three Kinects).

The reason why I’m not releasing right now is that I’m still trying to optimize the “user experience” by integrating the ideas I described in A Trip Down the Graphics Pipeline. The idea is that plugging in a Rift and starting a Vrui application should just work. I have most of that going; the only issue is telling OpenGL to sync to the vertical retrace on the Rift’s display, no matter what. Right now that can only be done via environment variable, and I’m looking for the right place in Vrui to set that variable from inside a program. It’s a work-around until Nvidia expose that functionality via their NV-CONTROL X extension, or, even better, via a GLX extension (are you listening, Nvidia?). Or, why not change the implementation of GLX_SGI_video_sync, which is already bound to a display and drawable, such that it always syncs to the first video controller servicing that drawable? Wouldn’t even require a specification change. Just an idea.

And last but not least, once I got the DK2 and its low-persistence screen working, I realized how cavalier I’ve been about low-level timing issues in Vrui. With screen-based VR and LCD-based HMDs it has simply never been an issue before, but now it’s pretty obvious. Good thing is, I think I have a handle on it.

In summary: it’ll be a little bit longer, but I’m on it. Will I be able to release before Oculus does their Linux SDK? Sure hope so! And just in case you think I’ve been sitting on my hands for the last six months: there are already about 300 large and small changes between 3.1-002 and 3.2-001.

And here is today’s unrelated picture:

Quikwriting with a Thumbstick

In my previous post about gaze-directed Quikwriting I mentioned that the method should be well-suited to be mapped to a thumbstick. And indeed it is:

Using Vrui, implementing this was a piece of cake. Instead of modifying the existing Quikwrite tool, I created a new transformation tool that converts a two-axis analog joystick, e.g., a thumbstick on a game controller, to a virtual 6-DOF input device moving inside a flat square. Then, when binding the unmodified Quikwrite tool to that virtual input device, exactly the expected happens: the directions of the thumbstick translate 1:1 to the character selection regions of the Quikwrite square. I’m expecting that this new transformation tool will come in handy for other applications in the future, so that’s another benefit.

Gaze-directed Text Entry in VR Using Quikwrite

Text entry in virtual environments is one of those old problems that never seem to get solved. The core issue, of course, is that users in VR either don’t have keyboards (because they are in a CAVE, say), or can’t effectively use the keyboard they do have (because they are wearing an HMD that obstructs their vision). To the latter point: I consider myself a decent touch typist (my main keyboard doesn’t even have key labels), but the moment I put on an HMD, that goes out the window. There’s an interesting research question right there — do typists need to see their keyboards in their peripheral vision to use them, even when they never look at them directly? — but that’s a topic for another post.

Until speech recognition becomes powerful and reliable enough to use as an exclusive method (and even then, imagining having to dictate “for(int i=0;i<numEntries&&entries[i].key!=searchKey;++i)” already gives me a headache), and until brain/computer interfaces are developed and we plug our computers directly into our heads, we’re stuck with other approaches.

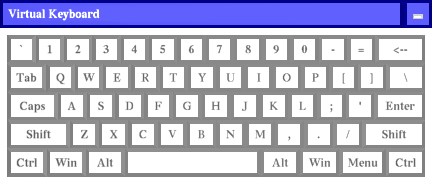

Unsurprisingly, the go-to method for developers who don’t want to write a research paper on text entry, but just need text entry in their VR applications right now, and don’t have good middleware to back them up, is a virtual 3D QWERTY keyboard controlled by a 2D or 3D input device (see Figure 1). It’s familiar, straightforward to implement, and it can even be used to enter text.

Someone at Oculus is Reading my Blog

I am getting the feeling that Big Brother is watching me. When I released the inital version of the Vrui VR toolkit with native Oculus Rift support, it had magnetic yaw drift correction, which the official Oculus SDK didn’t have at that point (Vrui doesn’t use the Oculus SDK at all to talk to the Rift; it has its own tracking driver that talks to the Rift’s inertial movement unit directly via USB, and does its own sensor fusion, and also does its own projection setup and lens distortion correction). A week or so later, Oculus released an updated SDK with magnetic drift correction.

A little more than a month ago, I wrote a pair of articles investigating and explaining the internals of the Rift’s display, and how small deviations in calibration have a large effect on the perceived size of the virtual world, and the degree of “solidity” (for lack of a better word) of the virtual objects therein. In those posts, I pointed out that a single lens distortion correction formula doesn’t suffice, because lens distortion parameters depend on the position of the viewers’ eyes relative to the lenses, particularly the eye/lens distance, otherwise known as “eye relief.” And guess what: I just got an email via the Oculus developer mailing list announcing the (preview) release of SDK version 0.3.1, which lists eye relief-dependent lens correction as one of its major features.

Maybe I should keep writing articles on the virtues of 3D pupil tracking, and the obvious benefits of adding an inertially/optically tracked 6-DOF input device to the consumer-level Rift’s basic package, and those things will happen as well. 🙂

Fighting Motion Sickness due to Explicit Viewpoint Rotation

Here is an interesting innovation: the developers at Cloudhead Games, who are working on The Gallery: Six Elements, a game/experience created for HMDs from the ground up, encountered motion sickness problems due to explicit viewpoint rotation when using analog sticks on game controllers, and came up with a creative approach to mitigate it: instead of rotating the view smoothly, as conventional wisdom would suggest, they rotate the view discretely, in relatively large increments (around 30°). And apparently, it works. What do you know. In their explanation, they refer to the way dancers keep themselves from getting dizzy during pirouettes by fixing their head in one direction while their bodies spin, and then rapidly whipping their heads around back to the original direction. But watch them explain and demonstrate it themselves. Funny thing is, I knew that thing about ice dancers, but never thought to apply it to viewpoint rotation in VR.

Figure 1: A still from the video showing the initial implementation of “VR Comfort Mode” in Vrui.

This is very timely, because I have recently been involved in an ongoing discussion about input devices for VR, and how they should be handled by software, and how there should not be a hardware standard but a middleware standard, and yadda yadda yadda. So I have been talking up Vrui‘s input model quite a bit, and now is the time to put up or shut up, and show how it can handle some new idea like this.

More on Desktop Embedding via VNC

I started regretting uploading my “Embedding 2D Desktops into VR” video, and the post describing it, pretty much right after I did it, because there was such an obvious thing to do, and I didn’t think of it.

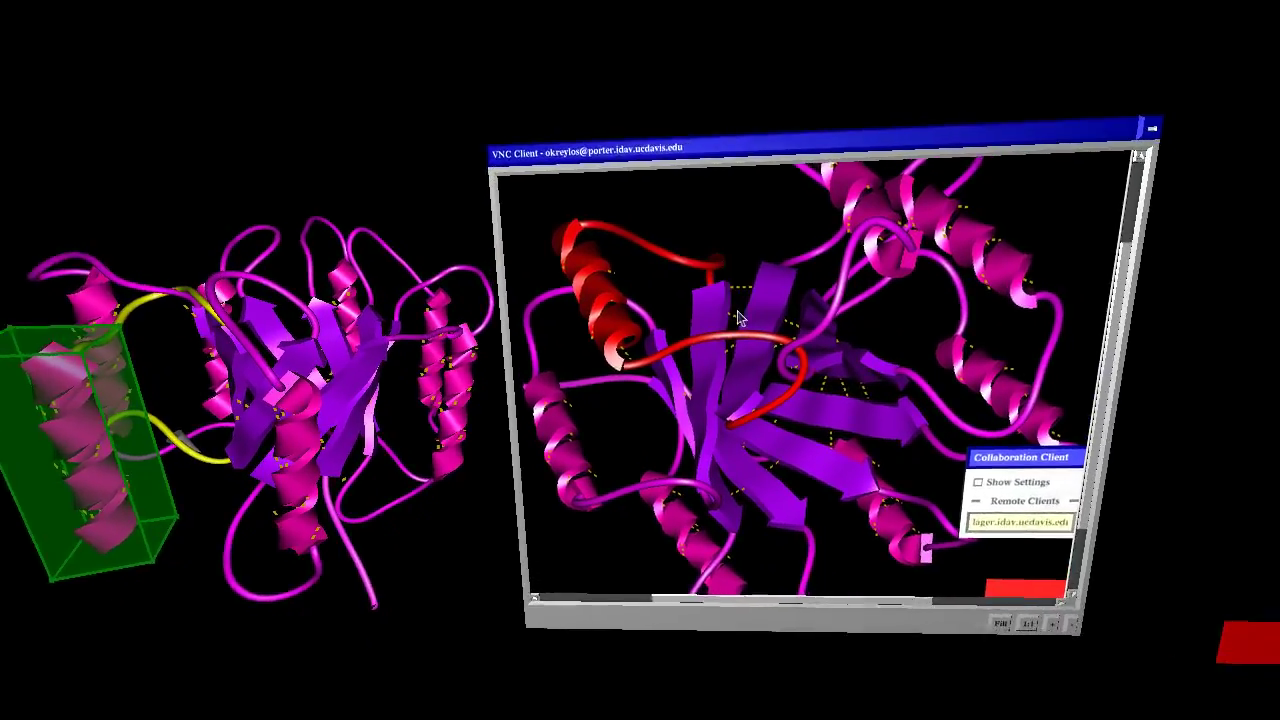

Figure 1: Screenshot from video showing VR ProtoShop run simultaneously in a 3D environment created by an Oculus Rift and a Razer Hydra, and in a 2D environment using mouse and keyboard, brought into the 3D environment via the VNC remote desktop protocol.

2D Desktop Embedding via VNC

There have been several discussions on the Oculus subreddit recently about how to integrate 2D desktops or 2D applications with 3D VR environments; for example, how to check your Facebook status while playing a game in the Oculus Rift without having to take off the headset.

This is just one aspect of the larger issue of integrating 2D and 3D applications, and it reminded me that it was about time to revive the old VR VNC client that Ed Puckett, an external contractor, had developed for the CAVE a long time ago. There have been several important changes in Vrui since the VNC client was written, especially in how Vrui handles text input, which means that a completely rewritten client could use the new Vrui APIs instead of having to implement everything ad-hoc.

Here is a video showing the new VNC client in action, embedded into LiDAR Viewer and displayed in a desktop VR environment using an Oculus Rift HMD, mouse and keyboard, and a Razer Hydra 6-DOF input device:

A Closer Look at the Oculus Rift

I have to make a confession: I’ve been playing with the Oculus Rift HMD for almost a year now, and have been supporting it in Vrui for a long time as well, but I haven’t really spent much time using it in earnest. I’m keenly aware of the importance of calibrating head-mounted displays, of course, and noticed right away that the scale of virtual objects seen through the Rift was way off for me, but I never got around to doing anything about it. Until now, that is.